Book and Lyrics by

Jacinda Duffin & Laurie Flanigan

Music by James Kaplan

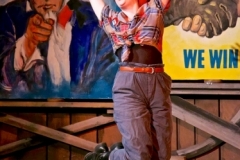

In this buoyant comedy set in Sturgeon Bay’s shipyards, Roxie and Anne, two hometown women, trade their regular lives for welding torches to help in the war effort. This show has been called “a love letter to ‘The Greatest Generation’.”Loose Lips Sink Ships recognizes and pays tribute to their sacrifice, their willingness to work for the greater good, their love for this country and, most important, their courage. Come hear their stories set to song!

Produced in 2001, 2002, 2006 & 2013

JSOnline.com

Mike Fischer, Special to the Journal Sentinel - June 24, 2013

American Folklore Theatre Casts Magic Spell (Part 2)

Fish Creek — In the late 19th century, a wide-eyed boy goes to sea and becomes a man. During World War II, a young woman learns how to weld and discovers a resilience she didn't know she had. Somewhere on Green Bay, two lonely fishing guides finally lose their fear and find each other.

Those are the stories being staged this summer at American Folklore Theatre, where scandalously cheap ticket prices allow an entire family to enjoy original musicals that combine G-rated entertainment and big-hearted, often sophisticated explorations of adult themes — all of it unfolding outdoors, in the woods and under the stars in Door County's Peninsula State Park.

Honoring the Greatest Generation

Last staged at AFT in 2006, "Loose Lips Sink Ships" is also divided between men at sea and those left behind, but this time the focus is on the home front, where women entered factories in droves after Pearl Harbor, making the ships, planes and tanks that transformed Depression-era America into Roosevelt's Arsenal of Democracy.

While writing the book and lyrics, Jacinda Duffin and Laurie Flanigan interviewed more than 20 people, including women who had worked in the Sturgeon Bay shipyards where much of "Loose Lips" is set. It shows. All of the characters in "Loose Lips" ring true, and James Kaplan's terrific score adds emotional heft to their stirring, sometimes heartbreaking story.

"Loose Lips" revolves around Roxie Tachovsky (Rhode) and Anne Hillstrom (Shine), both of whom become welders after the men down their tools and pick up weapons.

Roxie is a natural; even before donning pants and a welder's helmet, she works in the shipyard's personnel office and holds her own with the men, regularly cleaning their clock at the poker table and giving as much guff as she gets. Straddling the line between puckish and acerbic, Rhode is perfect for the role.

Anne is another story.

When the bombs fall on Hawaii, Anne is on the cusp of marrying Jack (Luberger) — never questioning his view that a woman's place is in the home. We first meet her as a perfectly still porcelain doll being fitted in her mother's wedding gown — par for the course, with a woman holding her breath and trying to squeeze into a vanished past rather than striding into the future.

All that changes once Anne becomes a welder, and Shine sketches a compelling dramatic arc as we watch Anne grow, assuming a quiet confidence that never feels forced. As she does in "Windjammers," Shine does a remarkable job of staying within herself, allowing a change in her carriage, the determined set of her jaw or her expressive eyes to do all the talking.

Like Rhode, Shine can also sing; the two are great together in "Look at My Heart," a duet in which they express their surprise and pride in how they have changed and who they have become.

That theme carries over to "Read Between the Lines," in which Rhode and Shine are joined by the company — factory coworkers, uniformed men in the South Pacific and two adolescents falling in love — in a gorgeously harmonized tableaux, effectively staged by director and choreographer Pam Kriger.

In allowing each character to sing and stand alone while also illustrating what they share, "Read Between the Lines" is a microcosm of this show as a whole; "Loose Lips" gives all of its characters their moments, and the AFT cast makes every one of them count.

I won't soon forget watching a bashful bachelor (Lee Becker) using a sock puppet to reveal his feelings. A young airman (Teddy Warren) confessing in a letter how scared he is. His sweetheart (Kiersten Frumkin) plaintively singing how much she misses him. A smitten sailor (Chase Stoeger) joyously spelling out his newfound love through signal flags.

As some of these examples suggest, "Loose Lips" has its lighter moments; one could add a fun jitterbug scene, Stoeger pretending to be a duck and a slinky number in which Rhode gets to air her pipes.

But at its heart, "Loose Lips" is a poignant and emotionally complex homage to the men and especially the women of what we rightly remember as the Greatest Generation. Forget the beaches, fish boils and cherry pies. This show is reason enough to go north.

Dramatists Magazine

ED HUYCK - January 2002

Playwrights Find Inspiration in History Building a Shipyard Musical in Wisconsin

For the first time playwrights Laurie Flanigan and Jacinda Duffin, it didn't take long to realize they were at sea without radar.

The two had a great idea for a musical — a look at the women who manned the shipyards in the little Wisconsin city of Sturgeon Bay during World War II. They had a regional theatre interested in their work and they had a composer, James Kaplan, with more than a dozen shows to his credit. Flanigan and Duffin even had an outline for the show. But shortly into the first draft, they made an important discovery.

“We realized we didn't know what we were talking about,” Duffin says.

“I have no memory for history and the gaps in my knowledge were vast,” Flanigan adds.

The two began a period of research where they “camped out” at the local library, studied newspapers published by the shipyards in the 1940s, and conducted scores of interviews.

The research — along with numerous drafts and feedback — paid off with Loose Lips Sink Ships.

The musical played to sold-out audiences during the summer of 2001 at American Folklore Theatre in Door County, Wisconsin, and there is a strong chance it will be revived for the 2002 season.

During the three-year process, Flanigan and Duffin learned plenty about the craft of playwriting. They may have learned even more about the art of research.

The heart of their story is set in Door County, the rustic “thumb” of Wisconsin that juts out into Lake Michigan. Though known for its agriculture — it was once the cherry capital of the United States — Door County, with Lake Michigan to the east and Green Bay to the west, is a natural home for shipping and shipbuilding.

It's also the home for many artists and performers — including American Folklore Theatre. They company, based in the summer at an outdoor stage in Peninsula State Park in the town of Fish Creek, is dedicated to musicals with historical themes. AFT built a stable of creators for shows, including founders Fred “Doc” Heide and Fred Alley (who died last year), composer Kaplan and Second City founder Paul Sills. Flanigan got to know the creative staff very well when she performed with AFT for several seasons. Duffin, a Door County businesswoman, was a longtime fan of their work.

The spark for Loose Lips Sink Ships came in February 1999 in a Milwaukee hotel room where Flanigan, Duffin and Kaplan were playing cards following an AFT performance at the Milwaukee Repertory Theater. As they kicked around ideas, Flanigan remembered an “E for Effort” pin from World War II and that her grandfather had worked in a foundry during the war years. They knew that Door County had played a role in the homeland war effort. Encouraged by Kaplan, who had suggested earlier that the two consider writing a show, Duffin and Flanigan began to talk, and then to brainstorm.

Through her and Kaplan's connections to AFT, Flanigan knew the show had a possible home. After encouraging words from the company's artistic staff, they started an outline and a draft.

That's when they got stuck on the history. During the 1940s, the shipyards were pressed into action to build vessels for the United States' efforts. As with other manufacturers in the country, women were hired to work in the Sturgeon Bay yards. The playwrights knew the local angle would forge an even stronger connection for an AFT production.

The two backed up and began to research. Though they had used numerous archival sources — videos, books, and newspapers — the backbone of the work came from interviews with men and women who had lived through World War II. “I had no idea of the scope of the shipyards in Sturgeon Bay,” says Flanigan.

AFT co-founder Fred Heide says research is essential for the work he has done for the company, which has included everything from concert revues to full-fledged book musicals like Belgians in Heaven. “I always start that way and do months of research,” Heide says. “It gives the creative juices time to percolate. I never feel ready to jump in right away and do a show. It takes time to take seed and take root.”

He's traveled to Ireland, Scandinavia and Belgium, and talked with Wisconsin farmers. “People are possessors of this great wealth of knowledge. It can really be entertaining (to listen to them).”

They can also add specific details that bring a story to life. “It's one thing to read books, but it is more helpful to talk to individuals,” Heide says. “You get a real sense for what is real.”

Flanigan and Duffin talked to dozens of men and women involved in World War II activities — including a number of people who worked in the shipyards. “We put the word out and got a response almost immediately,” Duffin says. “We weren't quite ready to do the interviews, because we thought it would take longer (to find people).”

Duffin and Flanigan decided to ask about basic information — the when and where of employment — as well as the specifics about the day-to-day job, and to gather anecdotes about wartime experiences. From their interviewees, the playwrights learned shipbuilding terminology and slang, how long it took to build a ship, the proper way to weld a plate, what the women wore while working and other details that added depth to the show.

Early in the musical's development, Duffin and Flanigan decided to make the men who left town sailors, to connect with the shipbuilding theme. For some time, they didn't give much thought to what they would be doing out at sea.

“Laurie was in California interviewing this father of a friend of mine. He had been a radio operator teacher. There was a student in his class who was having trouble learning how to do Morse code. He helped to teach him using music,” Duffin says.

At the mention of music, Flanigan's ears perked up. “I called Jacinda and said, 'Morse code is like music!'”

They had a Navy job for their men — and an idea for a song. A sailor is trying to teach his friend how to use Morse code so he can become a radio operator. It doesn't work until he explains that the code is like music. The second sailor starts to get it, and the two break into the song “Dot's It! Da Di Da Dit.” “The scene wrote itself,” Flanigan says.

To top it off, Flanigan found a metal tapper for practicing Morse code at her father's house, and they used it in the show.

Other World War II stories sparked jokes and songs for the musical. For example, one woman told them about sending a cooked chicken (complete with trimmings) through the mail to her brother who was stationed on a ship in the South Pacific. The song “Chicken” — in which a sailor describes his growing love for a woman who would do such a lovely, but absolutely crazy, thing — became a standout moment in the musical.

By contrast, Kaplan did little specific research for Loose Lips, relying instead on his familiarity with various musical styles and tailoring the songs to the situations. An important scene, for instance, is set at a dance.

“I wanted (the music) to sound like songs that may have been played in the 1940s,” Kaplan says. There was one catch, though: the outdoor stage's small pit area only had room for only three musicians, limiting Kaplan's use of swing songs, which are best suited for a 30-piece big band.

After its successful maiden voyage, Loose Lips Sink Ships is being revised as Duffin and Flanigan prepare for the possibility of another production. Fortunately, one of the lessons they've learned about playwriting is simple — be a pack rat with the material. “Don't discard anything. At some point it may come back to you,” Duffin says.

Accuracy is also vital. “If you get something wrong, people will tell you,” Flanigan notes.

Writers, young and old alike, should pick topics that interest them. “What jazzes you is what you should write about. It will speak to someone,” Flanigan says.

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

DAMIEN JAQUES - July 2001

Ship Welders of WWII Spark A Riveting Script

AS A Green Bay high school senior in 1942, Betty Peterson was thinking beyond graduation. Her family didn't have much. She wanted to land a good-paying job. When Peterson learned that the Sturgeon Bay shipyards, 45 miles away, were desperate for production workers, she took a welding class.

Soon Betty the welder was crawling on hands and knees through small compartments in the bottoms of ships, with only a small bulb illuminating the way. When the bulb went out, she had to find her way out of the ship in darkness.

“I liked best welding the numbers on the outside of the ships,” she said. “It was outside work, and it was fascinating.”

With their fathers, husbands, boyfriends, and brothers serving in combat, millions of women entered the workforce during World War II, many in industrial jobs producing military equipment and supplies. Loose Lips Sink Ships, the new American Folklore Theatre hit packing the outdoor performance space in Fish Creek's Peninsula State Park, celebrates Wisconsin's counterparts to Rosie the Riveter — the women who worked in the Sturgeon Bay shipyards.

Sturgeon Bay's shipbuilding industry had turned the city into a boomtown during the war, with its four plants launching, on average, a ship every five days. Employment at the yards had exploded from 600 to 7,000, and manpower was so short, the yard owners turned to womanpower to build freighters, sub chasers and frigates for the war effort.

“I enjoyed welding,” Peterson said in a telephone interview from her Green Bay home. “There was pride in making a neat weld.”

There was romance, too.

Peterson met her husband, Percy, at the shipyard, where he was a foreman. They took their breaks eating ice cream under the ships they were building.

Betty's brother was in the Navy, and after a while, her boyfriend, Percy, joined. “I had two people to weld for,” she said.

With gasoline being rationed, a bus line was started between Green Bay and the Sturgeon Bay shipyards. Peterson had to walk only two blocks from her house to catch her ride. The buses also picked up workers at the little towns along the way.

The yards were cranking out ships around the clock, and Betty worked the second shift. “We would sing on the bus, and sometimes the bus would stop on the way home and we would all eat chicken at 11:30 at night. It was all ages. We had a good time.”

How it began

Although it throws a new spotlight on a proud time in Door County history, the musical was conceived in an unlikely musical setting 180 miles away.

“We were playing euchre in a room at the Plaza Hotel in Milwaukee,” said AFT composer-musician James Kaplan.

It was February of 1999. The players included Kaplan, AFT actress Laurie Flanigan and Door County businesswoman Jacinda Duffin. Kaplan was spending more time in Milwaukee as AFT shows were becoming hits on Milwaukee Repertory Theatre stages.

“Jimmy (Kaplan) had encouraged us for a long time to try writing a show,” Flanigan said. Over cards, the two women began kicking around possible subjects for a new musical.

During World War II, Flanigan's grandfather had worked in a Beloit foundry that supplied the defense industry, and she was intrigued by the “E” for effort pin he had been awarded. “AFT had been dominated by males, and I wanted to do a show about women,” Duffin recently recalled. She knew about the female welders of WWII, and she and Flanigan decided to make them the subject of their musical.

The women began researching their new musical, spending time at the Door County Maritime Museum and the Door County Library, where they pored through volumes of The Port Light, a company newspaper published by the Leathem D. Smith Shipbuilding Co. in Sturgeon Bay. They also conducted interviews with more than 20 people, including women who had worked in the yards.

Flanigan and Duffin laugh about the title of their show, because, well, they like to talk. And talk they did about the musical they planned to write. With Duffin running a restaurant and Flanigan waitressing there, it didn't take long for the word to spread throughout Door County.

An international workplace

The “loose lips sink ships” slogan was coined to remind people that a spy could be anywhere, gathering information that would lead to American casualties. The folks around the shipyards took the warning seriously.

“Everybody in Sturgeon Bay understood that nothing about what we were doing was to be said to anybody,” Betty Krueger recalled. “Nothing was printed in the (Door County) Advocate or in the (Green Bay) Press Gazette. A husband or wife was not supposed to talk to their spouse about anything that could be used against the war effort.

“The only loose lips we had were the kissing lips.”

A Sturgeon Bay native, Krueger was a teenager only a few months into her studies at Manitowoc Business College when Pearl Harbor was attacked.

Within several weeks, she was summoned home to interview for a job as the civilian assistant to the U.S. Navy lieutenant supervising the shipyards' war production. After the interview, she was asked if she could start work the next day.

Krueger's job included writing memos and checking billing to be sure the Navy was getting what it paid for, and supervising the young sailors who came to Sturgeon Bay to sail the new ships to their home ports after construction was completed. Not all the sailors were American.

The Sturgeon Bay yards built ships for the British, French, and Russian navies. “The Russians were so much cruder than the French, but the Russian boys were cute,” Krueger said. She recalled going to dinner with one of the French sailors.

“He couldn't speak any English, and I couldn't speak any French, but we had a good time chatting away.” The young Frenchman caught a lot of grief from his shipmates for going to dinner alone with the teenage Betty, so her mother invited all four sailors to a home-cooked meal.

Krueger, who joined the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) when she was 21, was chosen to christen a U.S. Navy ship, the PC1171, launched on May 15, 1943.

She spent a week deciding what to wear and used an empty ginger ale bottle to practice her christening swing. Krueger treasures a wooden box she was given to hold the smashed champagne bottle, which her mother threw away after it became moldy and started to smell.

“The war was a shock,” she said. “Sturgeon Bay wasn't the sleepy town it had always been. All of these strange people were suddenly here. The wages were good, but the living was hard.”

Sturgeon Bay was struggling with a severe housing shortage, and many staples were rationed.

Sore-eyed work

Dorothy Mosgaller grew up on a farm near Jacksonport in Door County, and her parents were pleased to have their daughter take up welding in the Sturgeon Bay shipyards. They had objected to Dorothy's previous job waitressing at a Fish Creek resort because the hours were long, the pay was low, and a tavern was connected to the hotel. Her welder boyfriend told her about “the nice-looking women who were working in the yards,” and Mosgaller decided in 1942 to take the welding basic training that was being offered in a garage in Sturgeon Bay.

Three years welding six days a week at the Leathem D. Smith plant was enough for Mosgaller, who later wrote in longhand her memories of the experience. “I didn't miss welding one bit. My eyes were so sore, I had to wear wet pads on them at night so I could go back to work the next day,” she recently said.

Mosgaller said that the welders worked in such close proximity to the ships, they couldn't avoid accidentally catching the bright welding flashes in their eyes when they lifted their helmets.

Her notes reveal that 534 women worked in production at Leathem D. Smith, the largest of the Sturgeon Bay yards. “Some men would get mad if a woman got an easier job or a better job,” she recalled in the interview.

“I don't know if anyone had a good time. We felt it was something we all should do. We were obligated.”

After the war

Peterson was laid off from the shipyard at the end of the war, and despite enjoying welding and being good at it, she never again put on the welder's helmet. She and her husband started a construction equipment business with a repair department that included welding, but she was not tempted to pick up the torch.

“I never thought of going back to welding,” she said.

Their research personally affected Flanigan, Duffin, and Kaplan, who are all in their 30s.

“I have a real sense now of how much I did not know about what it is to be patriotic, what it is to be so unified as a country.” Flanigan said.

Duffin spoke of her and Flanigan's discovery that they had much in common with the women of the shipyards. “We started interviewing old women and we wound up interviewing women just like us who had grown old.”

The writing partners also learned that their generation owes something to the women who crawled through ship hulls on their hands and knees. “One woman told us, 'my life eventually went back to the way it was before the war, but I raised my daughter differently,'” Duffin said.

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

DAMIEN JAQUES - JULY 2001

It's Smooth Sailing at Launch of 'Loose Lips Sink Ships'

In an understated way, Loose Lips Sink Ships, the new American Folklore Theatre musical that is a hot ticket here, is about legacy.

The hard work and sacrifices made by the people of northeastern Wisconsin during World War II is its backdrop. The groundbreaking women who worked as welders building warships in the Sturgeon Bay shipyards are represented in the show's story.

And although the late Fred Alley was not involved in the musical's creation or staging, Loose Lips Sink Ships floats on his style and sensibilities. Alley was a key contributor in the rise of the American Folklore Theatre, and he lives on in this production.

First-time writers Laurie Flanigan, an AFT actress, and Jacinda Duffin, working with company composer James Kaplan and Milwaukee director-choreographer Pam Kriger, have crafted a funny, warm, and ultimately touching one-act musical that distills the difficult choices and tragic realties faced by many Americans during World War II.

In the best traditions of AFT, the show contains the goofy lunacy of a singing sock, but also resonated with a gentle sweetness and vulnerability.

It is difficult to believe that Flanigan and Duffin are rookie lyricists, because their writing is polished, sometimes puckish, and produces strong images. “How do you wrap and send love?” asks a character, separated by war from her boyfriend.

20 songs in 90 minutes

The musical is chock-full of songs, 20 in 90 minutes, with some reflecting the period and other influenced more by Broadway. “The Strangest Thing,” a moving number at the end of Loose Lips, has a folk tinge.

As always, composer Kaplan's score is highly melodic and hummable, as easy to swallow as ice cream on a warm summer night.

Loose Lips centers on the romances of three couples. The men work at the Sturgeon Bay shipyards before the attack on Pearl Harbor. They join the service when the U.S. enters the war, and two of the women left behind keep the home fires burning by welding in the yards.

The characters respond differently to their new situations and experiences, and it is their evolution that makes the show genuine and interesting.

Kriger's choreography and direction, including a fun jitterbug number, is typically clever.

All of this is propelled by sharply drawn and distinctive performances provided by Flanigan, Treva Tegtmeier, Jon Hegge, and Doug Mancheski. When Jeffrey Herbst's sailor character receives a “Dear John” letter, he beautifully sings his feelings with a palpable hurt.